Image du Jours -- Early Aviation

About Early Aviation -- #7 of 7.

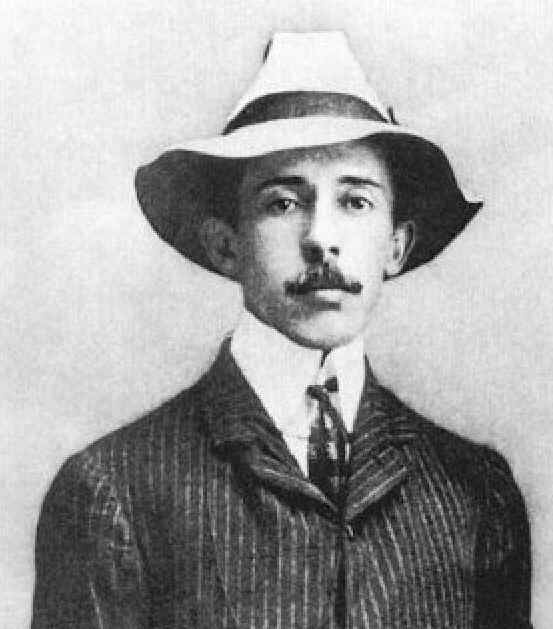

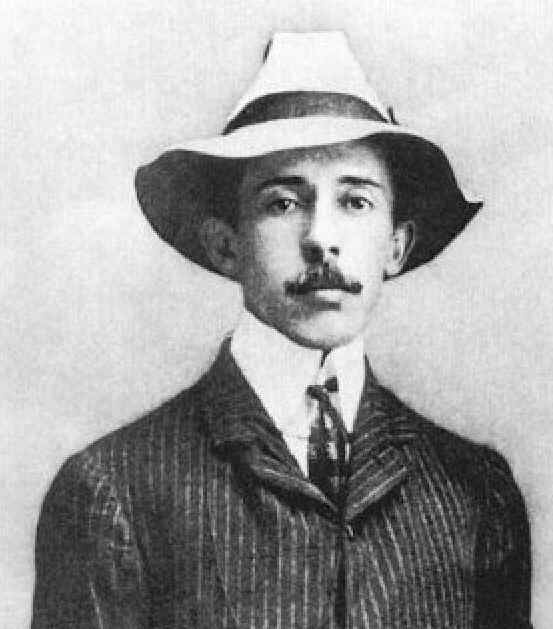

BIG MAN IN THE AIR -- Alberto Santos-Dumont

As is often the case when writing on a particular subject, the theme broadens and there is another facet that should be explored.

Aviation enthusiasts can name aircraft, engines, and specifications by the hour, and in a few cases we can say something about Chuck Yeager or "Pappy" Boyington -- or Erick Hartmann or Robert Johnson -- or Claire Chenault or Tex Hill – Mickey Mannock or Ernst Udet -- some of these are getting a little distant, but there is one aviator that most everyone should know.

Louis Bleriot, I've written about -- Charles Rolls and the Wright Brothers, but this a little paean to a special, early aeronautist -- Alberto Santos-Dumont. The name might look familiar but that might be all many can recall. He came from the most unlikely place for early aviation -- Brazil. He was born into a wealthy Brazilian coffee family in Sao Paulo in 1873.

On a morning in August of 2000, I was arriving in Sao Paulo, Brazil. The sun was just rising and illuminating only the tops of the tall buildings projecting through low, flat fog. The blue-gray of the haze and the silver and gold of the reflected sun on the sides of the buildings were quite striking. Sao Paulo is one of the largest cities in the world and for a long time we were flying low over a lot of it. I had Alberto Santos-Dumont in my thoughts then, and as this is read, it might become apparent why.

In September 1898, 25-year-old Alberto piloted the first of many airships he built. It was 82' long, filled with hydrogen and had a gasoline-powered motor precariously attached to the back of the suspended wicker basket. Alberto was wedged in the basket.

Before his first flight, fellow balloonists told him that the wind would tear him and the balloon to shreds. They pointed out that it was difficult to even hold the thing in one place on the ground. Alberto, nonplussed, said that once he was free of restraining earth, the balloon would be in its element and everything would go swimmingly. They released him and his airship, and sure enough, Alberto was right. He went cruising off at 1,300' to a nearby town so he could show everyone how easy flight really was.

His father had an accident and moved the family to Paris. This put Alberto in his element. The excitement of Paris and his wealth contributed to his continued interest in aviation.

In 1901, in his balloon, he won a 100,000 franc prize by being the first person to fly the 6.75 miles from a small field outside of Paris to the Eiffel Tower. It took him 30 minutes. Airships were not very fast, but the aeronautist had plenty of time to view the countryside.

Alberto had one peculiarity that drove the other fliers and manufacturers mad -- particularly, the stodgy English -- he insisted on dressing to the hilt in the most modern Paris fashions. Some were a little extreme. He would arrive for a flying demonstration in the largest carriage or car available and step out looking like something from a men's' fashion poster. He wore patent leather shoes, tailored suits and an exotic "sportsman" cap or straw hat -- his caps and hats were oversized, making him look smaller than he was. His gloves were white, spotless, and the wide tops went nearly to his elbows. His spats were always clean.

Parisians got used to his powered balloons clattering in the city skies, but in the summer of 1903, they heard a loud explosion and looked up. They saw an overly-rich engine sending long flames down the side of the hydrogen-filled balloon. They had seen enough of these failures to know what was going to happen to their new hero.

He took off his straw hat and started beating at the flames. Finally, the flames were gone and only a small amount of smoke was seen. He put on his beat-up, frayed, soot-covered hat and gave the shrieking crowds, repeated, cavalier waves and gestures with his once-white, gloved hands. Then he tipped his tattered hat to them and continued his flight across Paris. (I just have to love this guy!)

In 1908, with a heavier-than-air aeroplane of his own design, he flew the first such flight in Europe. He won a prize for flying 722 feet in 21.5 seconds. This aircraft was a monstrous biplane canard, the Santos #14 bis. It had a 43' long fuselage and the plane was over 11' high. The engine was the 50-hp Levassor. This was the same engine in the good-flying Antoinette. It never flew higher than ground effects permit; 10 to 20 feet for that aircraft.

Many consider that he should be credited with the first, heavier-than-air flights because the Wright brothers used gravity to take-off. They dropped a large weight to help catapult the plane into the air. Using gravity for flight is the same motive power for their earlier gliders. They left a hill top to glide to the bottom, so their aircraft were powered gliders...so say many. Santos-Dumont's plane rolled and accelerated along the ground under its own power to lift off.

But it was his Santos #20 that was his greatest plane and for which he had the most hope. The diminutive Demoiselle was simply a good-flying little airplane with its bamboo construction and familiar layout, yet the controls of the original were a little strange. A control stick for his right hand controlled the elevator; the wing warping was accomplished by a wheel mounted to his left and parallel to the centerline of the airplane. The rudder was controlled by pushing and twisting with his back against a right and left board.

And little, it was. Demoiselle had a wing span of just 18' and was only 4' high. Its twin-cylinder engine developed 24 hp and this resulted in an all-up weight of a mere 210 pounds. Alberto, weighing just 110 pounds himself and being but 5' tall, was called "Le Petit" by the French press. With his Demoiselle, he was often airborne in 230' and once he covered 5 miles in 5 minutes. He flew all over Paris at tree-top level and landed on the park area at boulevards and enjoyed sidewalk cafes.

He was popular with the press, giving them good quotes and aviation details. He generally charmed everyone and he was a constant proponent of future aviation. No one touted this new dimension more, and though he was very disappointed not to have been the first (credited) for flying such aircraft, he, personally, by his own enthusiasm and promotions, was going to put every man in the air with their own flying machine. This wasn't hype; he believed it!

He started manufacturing the Demoiselle ready-to-fly -- including instructions -- for 7,500 francs, which was a modest sum for the day. However, he was out-marketed by larger, faster aeroplane builders. This was when few of those airplanes flew as well as the Demoiselle.

Alberto operated independently because he could afford to. A lot of the others in aviation did not appreciate this coffee millionaire upstaging them, so he was often accused of being a showman and spendthrift. But by being a showman, he was promoting aviation when some of the others were becoming snobs and playboys. And he did put on a good show -- buzzing people gathering on roof tops -- with the Demoiselle, he might appear most anywhere.

Finally, Bleriot, Farman, Voisin, and others were making bigger, more powerful, and expensive airplanes, and aviation was rapidly becoming only the rich-man's hobby.

At just 37, Alberto, disillusioned with his fellow aeronautists' elitism, announced that "aviation no longer needs me" and retired to his home near Paris. And he was despondent over developing multiple sclerosis

He had spoke...preached...about how soon, each man would have such a "dove" as his aeroplane and each man would, like an angel, look down on beautiful fields, valleys and villages just as he had. But aviation was developing in a little different direction now. No one could persuade him to stay in aviation, yet with the exception of the Wrights, he probably knew more about aeronautics than anyone.

In WWI, he was aghast at how quickly his doves had become birds of prey. He had said that aeroplanes would bring rare pleasure; now they were bringing common death.

Alberto did get to see some of the glory he had hoped for when he was present to welcome Lindbergh as he arrived in Paris after his solo flight.

Finally, in 1928, he was tired of Europe and just wanted to go home to the peace and solitude of his Brazilian coffee farms. Yet, when he came within sight of Brazil, his ship was met by a flotilla of journalists and well-wishers. They all pressed him for comments. He just wanting to be let alone. He was a very sick man and was almost forced to the bridge. It was announced that, in his honor, a new flying boat had been named for him. The flying boat came flying low by the ship, then right in front of Alberto, a wing clipped the water and it crashed, killing the crew and passengers.

Two years later, more than 50 passengers burned to death in an air accident and he felt responsible for each one.

Terribly depressed, he tried to kill himself but friends intervened. He said repeatedly that he had wanted men to be free and fly and he had brought them death. He should have enjoyed his age, money, and fame, but instead he became even more melancholy as his health deteriorated.

Then in 1932, revolution broke out in Brazil and the president launched air attacks against the rebels in Sao Paulo. Alberto saw first-hand, Brazilians dropping bombs on Brazilians from heavier-than-air flying machines.

Shortly after this, just three days after his 59th birthday, the sick little man, Alberto Santos-Dumont, hanged himself. He had gone from a dapper, aviation genius and the toast of Parisian society, to become a guilt-ridden, sick and bitter old man, alone and hanging in a room.

Alberto Santos-Dumont deserves that we remember him for the petit Demoiselle and his contributions to early aviation. His birth date was July 20, 1873. Ninety-six years later to the day, Neil Armstrong, engineer and model maker, stepped foot on the moon.

Ken Cashion